Un paisaje lunar polvoriento imaginado por el Laboratorio de Conceptos Avanzados de la NASA. Crédito: NASA

El calor del sol es bienvenido en un día frío de invierno. Sin embargo, a medida que la humanidad emite más y más gases de efecto invernadero, la atmósfera de la Tierra captura más y más energía solar y aumenta constantemente la temperatura de la Tierra. Una estrategia para revertir esta tendencia es interceptar parte de la luz solar antes de que llegue a nuestro planeta. Durante décadas, los científicos han buscado usar pantallas, objetos o partículas de polvo para bloquear suficiente radiación solar, 1-2%, para mitigar los efectos del calentamiento global.

Un estudio dirigido por la Universidad de Utah exploró el potencial del uso del polvo para protegerse de la luz solar. Analizaron las diversas propiedades de las partículas de polvo, las cantidades de polvo y las órbitas que serían más adecuadas para dar sombra a la Tierra. Los autores encontraron que lanzar polvo desde la Tierra a una estación de paso en el «punto de Lagrange» entre la Tierra y el Sol (L1) sería más eficiente, pero requeriría costos y esfuerzos astronómicos. Una alternativa es usar polvo lunar. Los autores argumentan que la liberación de polvo lunar podría ser una forma barata y efectiva de ensombrecer la Tierra.

Un flujo simulado de polvo iniciado entre la Tierra y el Sol. Esta nube de polvo se muestra pasando a través del disco solar visto desde la Tierra. Dichos flujos, incluidos los flujos emitidos desde la superficie lunar, pueden ser escudos solares temporales. Crédito: Ben Bromley / Universidad de Utah

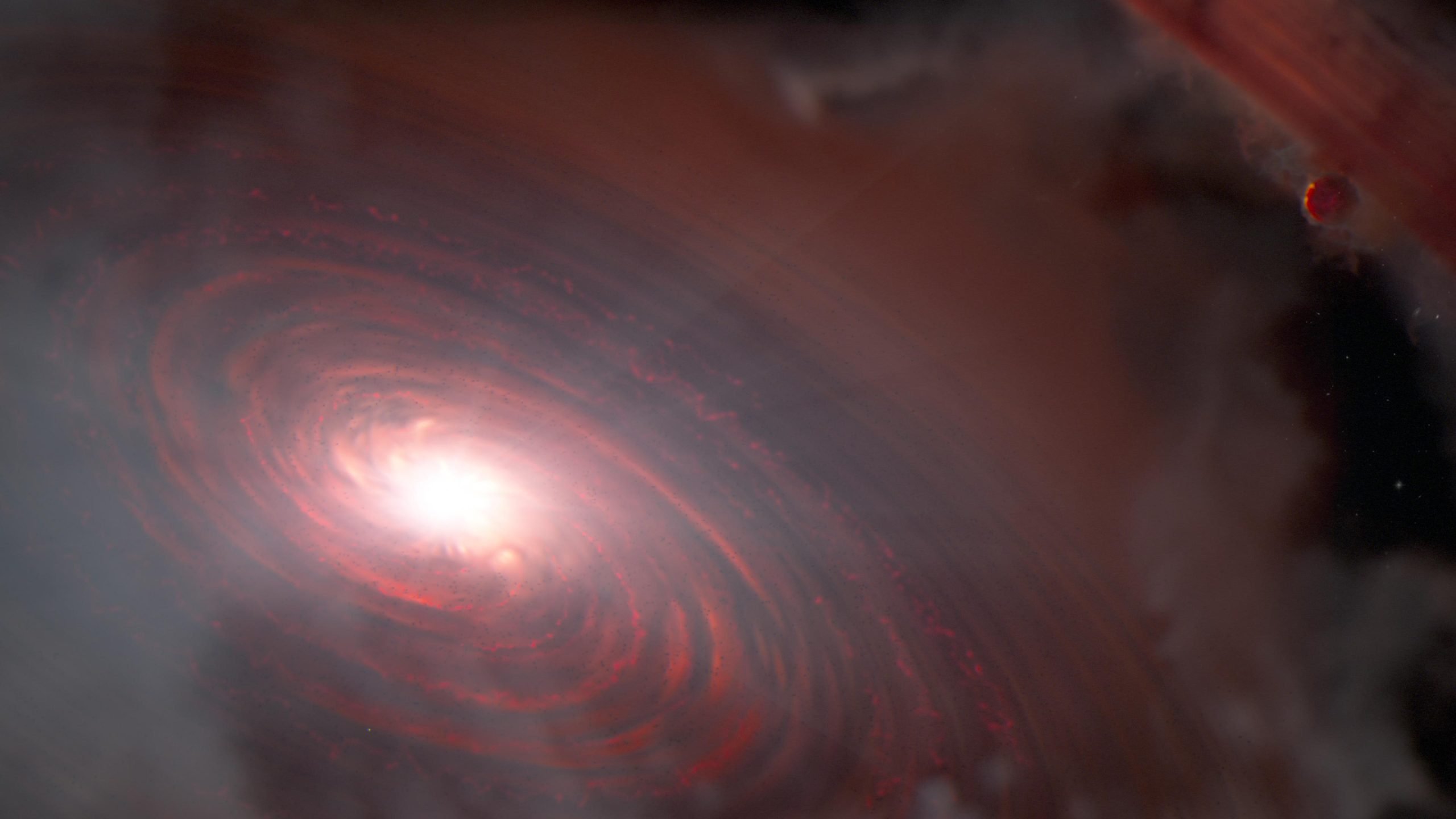

El equipo de astrónomos aplicó una técnica utilizada para estudiar la formación de planetas alrededor de estrellas distantes, su foco habitual de investigación. La formación de planetas es un proceso complicado que produce una gran cantidad de polvo astronómico que puede formar anillos alrededor de la estrella anfitriona. Estos anillos interceptan la luz de la estrella central y la vuelven a irradiar para que podamos detectarla en la Tierra. Una forma de encontrar nuevas estrellas formadoras de planetas es buscar estos anillos de polvo.

“Esa fue la semilla de la idea. Si tomáramos una pequeña cantidad de materia y la pusiéramos en una órbita especial entre la Tierra y el Sol y la dividiéramos, podríamos bloquear la luz solar con una pequeña cantidad de masa», dice el físico y profesor Ben Bromley. astronomía y autor principal del estudio.

Una simulación de polvo lanzada desde una estación de paso en el punto 1 de Lagrange. La sombra proyectada sobre la tierra está exagerada para mayor claridad. Crédito: Ben Bromley

«Es increíble pensar cómo el polvo lunar que tardó más de cuatro mil millones de años en formarse puede ayudar a frenar el aumento de la temperatura de la Tierra, un problema que nos llevó menos de 300 años desarrollar», dice Scott Kenyon, coautor del estudio. . estudio del Centro de Astrofísica Harvard y Smithsonian.

El artículo fue publicado recientemente en la revista PLOS Clima.

Proyectando una sombra

La eficacia general del escudo depende de su capacidad para mantener una órbita que proyecta una sombra sobre la Tierra. Sameer Khan, estudiante de pregrado y coautor del estudio, dirigió la investigación inicial, donde los orbitadores podrían mantener el polvo en su lugar el tiempo suficiente para proporcionar una sombra adecuada. El trabajo de Khan demostró la dificultad de mantener el polvo donde debe estar.

«Dado que conocemos las posiciones y masas de los principales cuerpos celestes de nuestro sistema solar, simplemente podemos usar las leyes de la gravedad para rastrear la posición del sol simulado a lo largo del tiempo en varias órbitas diferentes», dijo Khan.

Dos escenarios eran prometedores. En el primer escenario, los autores colocaron una plataforma espacial en el punto L1 de Lagrange, el punto más cercano entre la Tierra y el Sol donde se equilibran las fuerzas gravitatorias. Los objetos en los puntos de Lagrange tienden a permanecer en un camino entre dos cuerpos celestes, por cualquier motivo.[{» attribute=»»>James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) is located at L2, a Lagrange point on the opposite side of the Earth.

A simulation of dust launched from the moon’s surface as seen from Earth. Credit: Ben Bromley

In computer simulations, the researchers shot test particles along the L1 orbit, including the position of Earth, the sun, the moon, and other solar system planets, and tracked where the particles scattered. The authors found that when launched precisely, the dust would follow a path between Earth and the sun, effectively creating shade, at least for a while. Unlike the 13,000-pound JWST, the dust was easily blown off course by the solar winds, radiation, and gravity within the solar system. Any L1 platform would need to create an endless supply of new dust batches to blast into orbit every few days after the initial spray dissipates.

“It was rather difficult to get the shield to stay at L1 long enough to cast a meaningful shadow. This shouldn’t come as a surprise, though, since L1 is an unstable equilibrium point. Even the slightest deviation in the sunshield’s orbit can cause it to rapidly drift out of place, so our simulations had to be extremely precise,” Khan said.

In the second scenario, the authors shot lunar dust from the surface of the moon towards the sun. They found that the inherent properties of lunar dust were just right to effectively work as a sun shield. The simulations tested how lunar dust scattered along various courses until they found excellent trajectories aimed toward L1 that served as an effective sun shield. These results are welcome news, because much less energy is needed to launch dust from the moon than from Earth. This is important because the amount of dust in a solar shield is large, comparable to the output of a big mining operation here on Earth. Furthermore, the discovery of the new sun-shielding trajectories means delivering the lunar dust to a separate platform at L1 may not be necessary.

Just a moonshot?

The authors stress that this study only explores the potential impact of this strategy, rather than evaluate whether these scenarios are logistically feasible.

“We aren’t experts in climate change, or the rocket science needed to move mass from one place to the other. We’re just exploring different kinds of dust on a variety of orbits to see how effective this approach might be. We do not want to miss a game changer for such a critical problem,” said Bromley.

One of the biggest logistical challenges—replenishing dust streams every few days—also has an advantage. Eventually, the sun’s radiation disperses the dust particles throughout the solar system; the sun shield is temporary and shield particles do not fall onto Earth. The authors assure that their approach would not create a permanently cold, uninhabitable planet, as in the science fiction story, “Snowpiercer.”

“Our strategy could be an option in addressing climate change,” said Bromley, “if what we need is more time.”

Reference: “Dust as a solar shield” by Benjamin C. Bromley, Sameer H. Khan and Scott J. Kenyon, 8 February 2023, PLOS Climate.

DOI: 10.1371/journal.pclm.0000133

Aficionado a los viajes. Lector exasperantemente humilde. Especialista en internet incurable

Impulsse.la Complete News World

Impulsse.la Complete News World